|

|

|

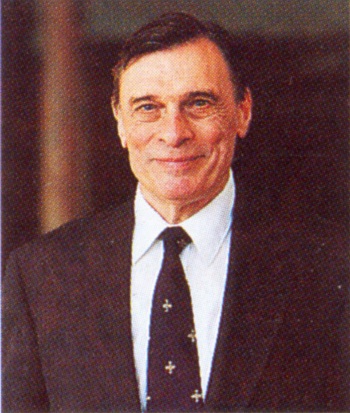

The charge of "ivory-tower academic" could never have been leveled against Denis Stevens. Although he was among the most respected of British musicologists, his research interests proceeded apace with his engagement in active music-making. Musicology was no isolated laboratory practice, but part of the living continuum that begins with what the composer leaves on paper and ends as it enters the listener's ear.

Stevens was born in High Wycombe in 1922 and attended the Royal Grammar School there. A scholarship took him to Jesus College, Oxford, in 1940 where he stayed for two years - studying languages, since the syllabus didn't then allow him to take a music degree - before Second World War service took him (and his violin) abroad. Shortly before he left, something occurred which would dictate the course of his life: he encountered Nadia Boulanger's pioneering recordings of the music of Claudio Monteverdi, now acknowledged as the most important Italian composer in the first half of the 17th century, but then just one little-known name among many. Between 1942 and 1946, Stevens served in RAF Intelligence in India and Burma, decoding Japanese transmissions, teaching languages to the airmen, and playing where he could - he sat among the fiddles of the Calcutta Symphony Orchestra when circumstances permitted. By the time he returned to Oxford a change of rules allowed him to study music proper. His principal teachers were Sir Thomas Armstrong, Sir Hugh Allen, R.O. Morris and Egon Wellesz, whose standing as a composer is only now beginning to be realized; in 1940s Britain, Wellesz's chief reputation was as one of the world's leading scholars of Byzantine music, and later Stevens would gratefully acknowledge the influence of Wellesz's historical approach on his own working methods. He remained at Oxford until 1949, combining the student life with playing the violin and viola in the Philharmonia Orchestra and in various chamber groups. Stevens was already making enough of an impact in early-music circles to join the BBC Third Programme in 1949 as producer and planner, turning down an orchestral violist's position in Scotland to do so. During the five years he stayed with the BBC he brought to air the rarer material for which that programme was created. In his autobiography he recalled his clear instructions from Lord Reith: "We know precisely what the public wants, and by Heaven they're not going to get it!" Thus Stevens obligingly supplied programs on Guillaume de Machaut, John Dunstaple, Guillaume Du Fay, Thomas Tallis and Monteverdi; his operatic productions for the Third Programme included Monteverdi's Orfeo and Marc-Antoine Charpentier's Médée, then both rare indeed. In 1952 Stevens' edition of The Mulliner Book, a unique anthology which encompasses English keyboard music from across the 16th century, inaugurated the series Musica Britannica. Another landmark in that year was Stevens' founding of the Ambrosian Singers, which he conducted for many years. In 1955 Stevens undertook a British Council lecture-tour of Italy to mark the Dunstaple quincentenary. In the same year a visiting professorship in musicology at Cornell University, in Ithaca, upstate New York, foreshadowed what would become the later pattern of his life: during the academic year he lectured, researched and wrote in the United States, and in the summer he would return to Europe to resume the role of the performing musician. A second visiting professorship, at Columbia University, New York, followed in 1956. Thereafter he came back to Britain, working again at the BBC and teaching at the Royal Academy of Music (where his portrait, by Evan Wilson, now hangs outside the main concert hall). After a year there, the death of Eric Blom left vacant the editorial chair of Grove's Dictionary of Music and Musicians, and Stevens duly occupied it from 1959 to 1963. He continued to fire on all fronts, introducing the first course in musicology to the Royal Academy in 1960, founding the Accademia Monteverdiana (a baroque chorus and orchestra) in 1961, and performing with them across Europe, in festivals as prestigious as those of Edinburgh, Gstaad, Salzburg, Lucerne, Bath, Bordeaux and Lisbon, as well as on radio and television and in the recording studio: his final tally of recordings exceeds 75. In 1962 another visiting professorship in the United States, at the University of California (Berkeley), proved the first of a distinguished series: Pennsylvania State University, 1962-63; Professor of Musicology, Columbia University, 1964-76; University of Washington, Seattle, 1976; University of Michigan, 1977; San Diego State University, 1978. All the while the articles, books, editions and recordings poured from him. Among the British composers on whom he wrote are Tallis, Henry Purcell and Thomas Tomkins; he produced editions of Robert Carver, Robert Fayrfax, Tallis and early Tudor organ music. And although he furnished an edition of Francesco Cavalli's hitherto unknown opera Pompeo Magno, among Italian masters it was above all Claudio Monteverdi who absorbed his attentions. Stimulated by his own requirements as a performer, Stevens produced new editions of the 1610 Vespers (in 1961 - the year in which he conducted it, in Westminster Abbey before an audience of 2,000), the Combattimento di Tancredi e Clorinda (1967), the Magnificat (1969) and, most recently, the Selva morale e spirituale (1998). In his later years in America he began to feel homesick and eventually returned to Britain, taking up a visiting professorship at Goldsmiths College, London University, in 1995, while residing at Morden College, an appropriately 18th century residence for retired academics. There, ignoring as far as possible his increasingly restricted mobility and macular degeneration of the eyes, he continued to work as best he could, organising his days with the energy and exactitude of his younger years. Anthony Pryer, Lecturer in Music at Goldsmiths, found Stevens' scholarship to be driven by a desire to find the real crux of the matter and overturn any attitudes that he thought were entrenched or habitual. Stevens could be obdurate on points of principle, but Pryer was eager to draw attention to his great interest in helping young scholars and performers and furthering the research he was interested in, especially Monteverdi. To that end, he bequeathed his entire Monteverdi library to Goldsmiths College. Stevens felt a mission to demonstrate the validity and accessibility of musicology as a discipline, often deploying what one former colleague called a "wry and penetrating sense of humor". He gave it full rein in an essay on the performance of the Monteverdi Vespers, complaining of "the cabalistic obscurantism that now surrounds it, fostered by misinformed musicians and pseudo-musicologists". He had absolutely no time for a misguided veneration of the past: "It is generally assumed that your first move, as conductor, would be to join an "auncient ynstrument clubbe" in order to organise exponents of "baroque" string instruments, harpsichords, lutes, theorboes, and sackbuts. Nothing could be further from the true aim and object. Not one of these flukes ever formed part of the instrumentarium of St Mark's, Venice, where Monteverdi was director of music from 1613 until 1643. They were never used in the basilica for the simple reason that the size and acoustic would make any one of them sound like a mouse breaking wind, and that is not what the composer wanted." Here we have the essential essence of Denis Stevens' great contribution to musicology: academia was always tempered by practicality and a great sense of humor. |

|

BMC 9 – Henry PURCELL Nine Trio Sonatas, 1697. Carl Pini & John Tunnell, violins Haroldl Lester, Gough harpsichord |

|

BMC 10 – Henry PURCELL Chamber & Incidental Theatre Music Music for Amphitryon, Distressed Innocence, Fairy Queen, Abdelazer. Trio Sonata, Harpsichord Suite, Violin Sonata. Fantasia on a Ground, and Overture in g. A varied program of music written to entertain, in theater or the home - and no less entertaining today! The Accademia Monteverdiana, Denis Stevens |

|

BMC 16 – VIVALDI: "La Cetra" Bk 1 Plus BOYCE: Two Concerti Grossi. This set of concertos was published by Vivaldi himself and dedicated to Austrian Emperor Charles VI. "Musically speaking, one of the finest and most interesting collections he has left us." (Peter Ryom). Also two early Concerti Grossi by Boyce, not to be confused with the (later) Symphonies. The Accademia Monteverdiana, conductor Denis Stevens |

|

BMC 17 – VIVALDI: "La Cetra" Bk 2 Plus ALBICASTRO: 2 Concertos. With Vol 2 of Vivaldi's "La Cetra" concertos, we offer two rarely (if ever!) heard concertos by the little-known Swiss composer Enrico Albicastro - unlike many baroque "discoveries" these are definitely worth hearing! The Accademia Monteverdiana, conductor Denis Stevens |

|

BMC 26 – TICKLE MY TOE Renaissance & Early Baroque Dances Six varied and tuneful programs of dances, capturing perfectly the mood of infectious gaiety and lively enjoyment. The Jaye Consort of Viols / Philip Jones Brass Ensemble Desmond Dupré, lute / Harold Lester, harpsichord The Accademia Monteverdiana Orchestra, Musical Director Denis Stevens. |